What Went Wrong in Cuba?

Disclaimer: Anything I might proclaim here about Cuba is incomplete, naive, and based on a dangerous combination of ignorance and idealism. I spent two short weeks in Cuba, only in a few neighbourhoods of Havana. My sources are a university graduate whom we paid twice to spend a few hours with us to answer our questions, a former Club Tropicana show dancer, an excellent Netflix miniseries (“Cuba Libre”) and a handful of brave taxi drivers and street vendors who shared guarded bits of their lives.

I say “brave” because speaking against the government is still, after six decades, a risky thing to do. For the same reason that I didn’t publish anything until after leaving, our university-graduate friend would have us shift positions in the park if someone came and sat too near. I’ll call her Maya - I would not dare to use her real name or photo.

“They’re poor but happy…”

After centuries, not just decades, of foreign domination and oppression, Cubans do indeed manage to find Joy. Rum, dancing, children, ice cream, baseball and boxing, guitars and cigars, thin folded-up pizza slices in the street, beautifully-kept gardens… so many outlets for the irrepressible will to live that has sustained this people through multiple uprisings, coups, Spanish and American colonization, food shortages and blockades.

“We have to laugh or we would just cry all the time, or give up,” says our guide Maya. Everyone speaks of the ongoing hardship of survival - running a side hustle to supplement insufficient government salaries and support, lining up daily for bread, staying connected to the neighbourhood gossip find out when a particular food or household item might actually be available, and making do when beans just aren’t available this month (nor last). No, nothing is substituted, they’re just not there.

Every Cuban is given a meager salary/pension averaging around 2,000 Cuban Pesos ($6 US at the current and rapidly devaluating black market rate that everyone uses). They also receive free housing (unless you’re single or from out of town, in which case you’re building a loft in your grandma’s room) and a ration card that entitles them to purchase from the government bodega a monthly supply of food and necessities, such as:

- 7 pounds of rice

- 4 pounds sugar

- 1 liter coffee

- 10 oz. yellow peas

- one bun per day

- one soap

- 5 eggs

- 1 pound of chicken.

Yes, 5 eggs and 1 pound of chicken per month.

Rare is the month that all items are available even from this meager list, which is already not enough to sustain a person for a month. If the bodega was fully stocked, the full rations at government-subsidized prices would use up about 700 of their 2000 pesos, leaving 1,300 to purchase everything else in private stores where items are 10-50 times above the subsidized bodega prices (and even those stores are unreliably stocked; it took us a week to find eggs). A flat of 30 eggs costs 3,300 pesos (remember, they only had 1300 for the month). A block of gouda cheese costs 2,000. A seat in a cramped shared taxi into town costs 200 pesos. My daily ice cream binge cost me a mere 75 cents (240 pesos), but on Cuban rations that’s 18% of their monthly survival budget.

Side Hustles

Surely you could live - not well, but survive - on what the government provides? I pushed and pushed Maya and others, but they resolutely responded it’s not possible. Everyone needs some extra income on the side. Just to get by - getting ahead is beyond dreaming for most.

Our retired national level dancer who once toured the world now cleans and manages the foreign-owned suite next door, and her husband takes extra restaurant shifts to get more tips. Maya leads these AirBnB Experience tours. Bodega workers accept “tips” for people to be served even after waiting 3 hours for rations. Our AirBnB host works high tech for a foreign firm to earn dollars, and still manages the suite and does airport taxi runs.

The biggest income supplement is remittance: over two-thirds of all Cubans on the island receive and rely on assistance from families abroad. When Maya asked her mother’s doctor if her heart condition was manageable, he answered with a question - “Do you have family abroad?” Only with access to foreign funds - in her case through her guiding work - could the medicines she needs to survive can be purchased. The dual economy creates dual realities - those with family abroad can afford medicine and food and even the occasional ice cream, while those without have to make do or do without.

On our way to the airport, we told our host that we had shared our leftover groceries with the retired couple a few floors down. He smiled and said how wonderful that was. “They work their whole lives for the country, then have to live on a pension of 1,500 pesos per month. They deserve so much more.” So humbling to know that the bag full of leftover eggs, veggies, honey and bread - so little for us - would mean so much to a couple who had helped create this brave new experiment since the revolution. People who should be venerated, not left to stand in line every day for their one fresh bun, and to make 10 ounces of green peas last a month.

The Good Old Days

It wasn’t always like this. The standard of living in the 1950’s was higher than most European cities. In the 1980’s, bodega shelves were full and people could get their full rations and have enough to live. Some bodegas still use the old signs that show the wealth of products they provided each month - now, most of the items have an X beside them, in chalk that could be erased but clearly hasn’t been for a long time. Fidel’s commitment to providing every Cuban with what they needed used to work, until the 1980’s.

I still believe that the intentions of the government are truly to serve the entire population - free medicare, 100% literacy, food and housing supplied. I still believe (choose to believe?) that they would better stock the bodegas if they had the means - it’s an economic problem. The US blockade hurts, and as always it hurts the poor the most. The collapse of the Soviet Union reduced their main source of aid, investment and trade. A subsequent alliance with Venezuela (primarily trading Cuban doctors for petroleum - Cuba’s largest export are doctors, who work overseas and remit 90% of their foreign salary to the Cuban government) filled gaps until that country hit their own woes.

So where did it go wrong? In hindsight, Cubans fought hard for liberation from Spain, only for that oppressor to be replaced by the US (government and mafia) and the dictator Batiste. When Fidel Castro’s “26 of July” movement broke those chains, they ended up becoming reliant on the USSR.

The biggest myth that was busted for me is the notion that Cuba had become self-reliant because of the blockade. There are some successful examples (doctor training, education, biotech), but overall the country has not succeeded in growing enough food, generating energy, manufacturing products enough to serve its people and/or maintain a healthy trade balance with partner countries. Yes, the blockade is a major factor - for example, there’s a lack of equipment and maintenance parts (the US even restricts all other countries from selling to Cuba any equipment with 20% or more of US-made parts), food and medicine imports are much more expensive because of having to come from overseas instead of the US, and a current shortage of fertilizer and animal feed has cut food production by 80% this year. But 60 years is a long time to not generate a thriving independent economy.

My fear for the future is that unrestrained capitalism will be seen as the only solution. When we asked Maya and taxi drivers and retired dancers what needs to happen, their genuine first response is to shrug and not believe anything can get better. When pushed, they point to allowing Cuban exiles to come back and invest, increased investment from Soviet business, and other external investment-oriented solutions, rather than internal investment in production and infrastructure. I’m not a smart-enough economist to understand what can truly lift a country, but I will choose to believe that it can happen while staying true to the revolution’s vision of serving ALL Cubans without the rapidly-increasing wealth gap that is the hallmark injustice of the United States and many other “developed” nations.

Tired, not Beaten

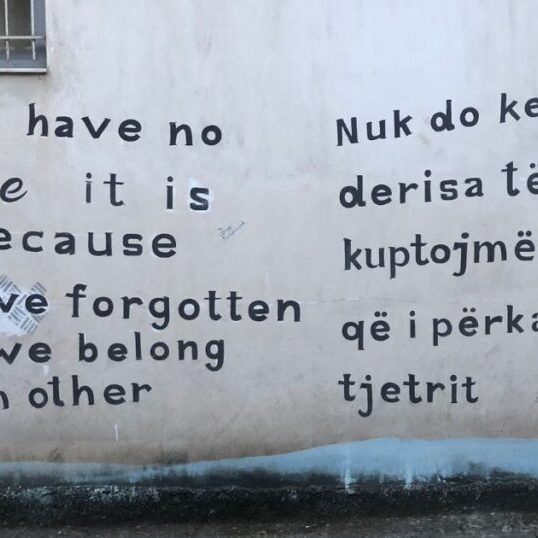

This daily Work to Survive, mixed with lack of hope/vision for the future, adds up to a general muted energy everywhere. People aren’t protesting, aren’t debating, aren’t even arguing. Memes are popular with young folk, but not with any call to action or even constructive ideas, just laughing at the situation. The most dissident movement we saw was the use of graffiti to question the gap between what the government says and what reality looks like. It takes the form of a simple equation in black spray paint on walls throughout Havana: 2+2=5?

People don’t talk or smile while waiting hours in line-ups every day for the bodega, for the subsidized Coppelia ice-cream (we waited 1 hour and the line-up of 457 people - I circled the entire city block to count - had barely moved), for the overcrowded bus, for drinking water (3 pesos/liter), for a free health check-up. Maya’s mother - a senior with heart problems - waits 3 hours a day for her bread and supplies. She is too tired to be a chatterbox, too discouraged to see the bright side of community-building in a water line like I used to enjoy in Tanzania. She just wants to get her damn water and get home. Maybe tomorrow there will be beans in the bodega.

Subscribe now to get an email notification when a new post is published.

(Be sure to check your inbox to confirm your subscription.)

Currently in...

Monteverde, Costa Rica, for 2 months of cloud forest and community

Heading to...

Chicago/Montreal for Christmas, then Thailand (Chiang Mai), Vietnam (Hoi Ann, Feb-Mar). Please share any sites, people or ideas by email.